From first (Lego) brick to final blow, the ruthless life of a hardware startup

It took me some time to write this mini post-mortem of my first startup, Kello. But here we are, 12 years after it all began and 6 years after it ended.

It's September 21st, 2016. I remember refreshing our Kickstarter page every few seconds, my heart pounding. I had never been this stressed in my entire life. A three-year journey was about to materialize. Had we built something people truly wanted? Would we be able to make it real? Or had I just made a huge mistake?

This is the story of how a simple idea turned into a mass-produced device, and how we navigated the unpredictable world of hardware startups.

This is the story of how we made Kello, the first alarm clock that will make you look forward to mornings.

The startup bug

Creating something from scratch has always felt natural to me. Maybe it ran in the family. Maybe I was lured by the dream of total freedom and financial independence that startups promise. Or maybe it was just the myth that drew me in.

Back in 2012, in France, the logic was simple: if California could do it, why couldn’t we? France had top-tier engineers, a strong economy, and a new wave of successful entrepreneurs from the early 2000s who were reinvesting their time and money in the ecosystem. It was the birth of the Startup Nation.

My brother and I had always talked about launching something together. We had the drive, we had some basic skills, we just needed the right idea, and capital. It seemed like it was the right time, so we decided to take the leap alongside a friend of my brother's.

Since I was a kid, I’ve been obsessed with electronics. I was that kid who dismantled every toy to see what was inside and forgot how to put them back together. My parents actually thought there was something wrong with me (they're still not sure about that). There is something magical about physical products, that you can touch, interact with, and see people using in their daily lives. Back then, SaaS was (and still is) all the rage, but we wanted to create something real, something people would fall in love with.

The "Aha!" moment

December 2012. A cold morning in Paris. The kind where the sun barely shows up, and staying under the covers feels like the only logical choice. I had a meeting at 7 AM, which of course meant waking up at 4:30 AM to execute my meticulously optimized morning routine.

The alarm clock screamed right on time. Groggy, annoyed, and already behind schedule for my sun salutation ritual, I grabbed my phone and did what any normal person does: opened Spotify and put on my favorite soft tunes playlist to reintroduce myself to the world. Namaste, Norah Jones.

And that’s when it hit me. Why the hell was I doing this manually? What if an alarm clock could just do it for me? And this is how Kello was born.

That's a bullshit story, obviously. We came with the idea of an alarm clock that would wake you up gently just because old-school alarm clocks were awful and everyone hates waking up with their phone alarm.

At the time, my brother was working at a music streaming company. He noticed a huge number of users were hacking their way into waking up with music (DIY setups, Bluetooth speakers, lots of frustration).

Yay, we had an actual problem on our hands! A data-driven problem! That's the best kind, according to the Y Combinator's videos we injected in our veins 2 hours a day! Plus the market was completely empty. No smart alarm clocks worked with Deezer or Spotify. So why not build one?

So we got to work. We had one goal: make something. Anything that we could show to investors as soon as possible.

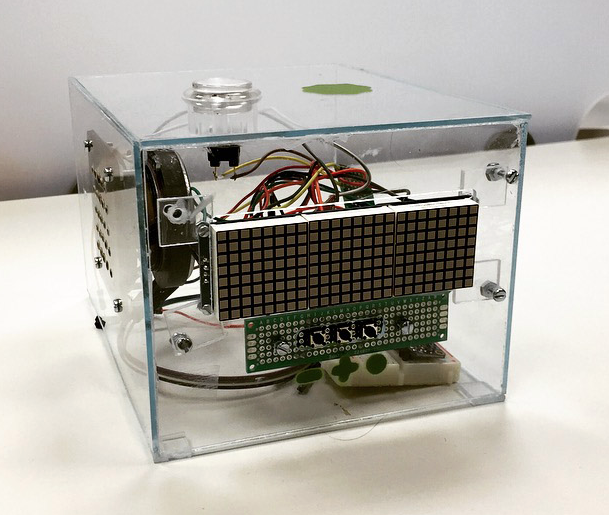

A Raspberry PI and plastic box, that's a lovely origin story for a hardware startup. It was ugly, slow, and barely worked. But it was enough to put onto a pitch deck and convince early investors. It didn’t need to be perfect, it just needed to exists.

The pitch that changed everything

In October 2013, we still had our day jobs and we bootstrapped prototypes just for fun. One day, I came across a tweet from one of France's most proeminents business angels about a startup pitch competition. The concept? 60 seconds to convince a jury and packed room of aspiring entrepreneurs, followed by 60 seconds of Q&A. If the jury was won over, they would inject €25,000 in cash (through a SAFE) into the project.

We took our shot, got pre-selected, and found ourselves in a packed Paris theater, surrounded by 300 other entrepreneurs, each carrying their own dreams and hopes. On stage: a screen, a single slide, and in front of us, the three biggest business angels in the country.

My turn came, I stepped onto the stage.

“Every morning, millions of people use their awful phone alarm to wake up. First thing they do? Put their favorite music on Deezer or Spotify. But there’s no smart alarm clock that can do this properly. We’re going to change that.”

I actually have no clear memory of my pitch or the questions. What I do remember is that we were the only ones presenting a hardware project among the 300 startups that day. A weak signal? Maybe. Anyway, I must have done something good because we walked away with the money and the confidence that we were onto something big.

With our first funding secured, we quit our jobs and jumped headfirst into prototyping. Actual prototyping. We worked out of coworking spaces across Paris, hacking together early versions of the product.

From Lego to luxury

We had to have a design for the product. One that would not look like a glorified Lego Mindstorms.

We chose to work with a successful French design company, who was designing beautiful furniture and novelty items at the time. After a few iterations, we had a final design.

Gorgeous, organic, simple. It was a nightmare to manufacture but a delight to the eyes.

Burning cash and eating glass

As they say, hardware is hard. But the actual truth is that making a hardware startup is a mix between staring into the abyss, eating glass and burning loads and loads of cash for the most trivial things. Ordering 50 prototypes? That will be $5k. Making a simple mold for silicone buttons? That's $8k. Having a neat design for your product? $15k, please.

And while you spend your money, you don't make revenue. There is no "fake it 'till you make it" in hardware. No revenue until you have paid for actual products to be put on shelves and hope for random persons with sleep issues will buy. You just have to pour hundreds of thousands of dollars to a Chinese company you don't really know, and pray to get the products at the end.

AND you have to make a product people want at the same time! Discovery journey, user interviews, user stories, the whole thing, knowing that don't have that much to show other than a shoebox. And people don't fall in love with shoeboxes. We did not have the skills. We realized we needed more support.

By the summer of 2014, we applied to a bunch of accelerators. A B2C hardware startup with no recurring revenue business model? That was a very long shot. But we got accepted into a lovely hardware accelerator in Hong Kong, China, approximately 30 km from Shenzhen, where all the consumer electronics of the world was manufactured. It was a no brainer.

So in August 2014, we packed our bags.

Living the startup grind in Hong Kong

We landed in August 2014, a 3D printer stuffed in our suitcase. The city was buzzing, and we got swept up in the energy right away. Our base camp? A tiny space in the accelerator's office, right in the middle of Hong Kong. From day one, we went all in. Long days, short nights, and way too many microwavable cheese sandwiches from 7-Eleven (I put on 15 kilos).

Startup life in Hong Kong was a crazy mix of non-stop excitement, sleepless nights, and full immersion in the hardware world. Our days were packed with prototyping, supplier meetings, and rooftop nights talking about how we were going to change the world. Everything moved insanely fast.

And just 30 kilometers away, Shenzhen was our playground. The dream spot for anyone trying to turn an idea into a real product. You were a phone call away from anything. It was surreal.

Pretty quickly, we realized raising money for hardware was going to be a challenge. VCs don’t like watching their cash turn into resistors and capacitors. What they want is scalable R&D, high-margin, high-traction. A consumer hardware startup? That didn't quite cut it.

A few hardware startups do manage to grab VCs’ attention, but only if they nail their business model. The trick is having solid revenue (recurring, if possible) and high enough barriers to entry so you don’t get copied in two months by some giant big tech or a factory in China.

So we had to find another way to finance the product.

Kickstarter was booming at the time. Pebble, Coolest Cooler, and other products were raising millions. If we wanted Kello to happen, this was our only chance. The principle is simple: you pay for the product at a jawdropping discount, you wait a few months (sometimes years, sometimes forever), and hopefully you get your product. The funds that were raised were used to pay for the product's R&D and the initial batch.

It’s not a fundraising round, it’s pre-orders, plain and simple.

The art of a killer Kickstarter launch

Our accelerator helped us tremendously. Marketing, go-to-market strategies, digital ads... We had courses on all those things.

We learnt that a great Kickstarter campaign doesn’t start on launch day: it starts months before. Kickstarter is like a rocket: you need huge initial thrust at launch, then hopefully the campaign will snowball into something huge.

So we built a landing page with sleek product renders. Then, we ran Facebook ads to collect emails. Every email cost us money, so the math had to work. We needed at least 10,000 subscribers to have a shot at making an impact.

We then sent out newsletters, keeping people hyped. We wanted them to feel were part of the journey, so we asked their input on features and they gave us lots of feedbacks, which is ideal for customer discovery.

We documented every step of the process on the Kello blog and built a real community by keeping people in the loop and posting numerous videos. And it worked. They got excited about the product, left dozens of comments on each blog post, and started asking when they could throw their money at it.

It took us 6 months to craft the campaign page. To seal the deal, we filmed a polished Kickstarter video in a luxury Hong Kong home. Everything had to look ultra premium.

The launch was just the beginning

September 2016. The big day.

We hit "Launch."

29 minutes later, we were fully funded.

By the end of the campaign, we had raised $360,000, enough to move into production. But crowdfunding isn’t free money, it’s a promise. Backers don’t invest in your company, they pre-order a product. And that meant we had to deliver.

That sentence sounds simple. It wasn’t.

Finding the right factory was a six-month phase of endless calls, factory tours, and one-on-one that felt more like dating than business. You can’t just Google “good factory in China” and expect to get an honest partner. Some looked legit but ghosted us after the second email. Others showed us beautiful showrooms, then giave us samples that looked like they came out of a Happy Meal box.

Eventually, we found a small factory in the Guangdong province that specialized in consumer electronics. They weren’t the cheapest, but they got us by understangin what we were building, had the right certifications and spoke solid English.

We had to fly out, walk the factory floor, and meet the engineers. It was clear: these people knew what they were doing. They’d built Bluetooth speakers, consumer electronics devices, even old-fashioned alarm clocks for American retailers. It was the perfect match.

But committing to a factory meant sending them loads of money before seeing a single finished unit. You pay for the tooling, the NRE (non-recurring engineering) costs, the test units. And if you mess up a spec, you pay to fix it. Talk about a leap of faith.

We spent weeks finalizing drawings, PCB layouts, materials, packaging. Every detail mattered. Would the plastic warp in the mold? Would the fabric scatter the LED light correctly? Would the button feel “clicky” enough? Each question led to more samples, more delays, and more invoices.

Despite the stress, there is nothing like seeing your product come off an assembly line for the first time. I still remember the moment I held the first production unit in my hands. Years of work, distilled into a single, working device. It wasn’t perfect. But it was real.

Shipping our first units

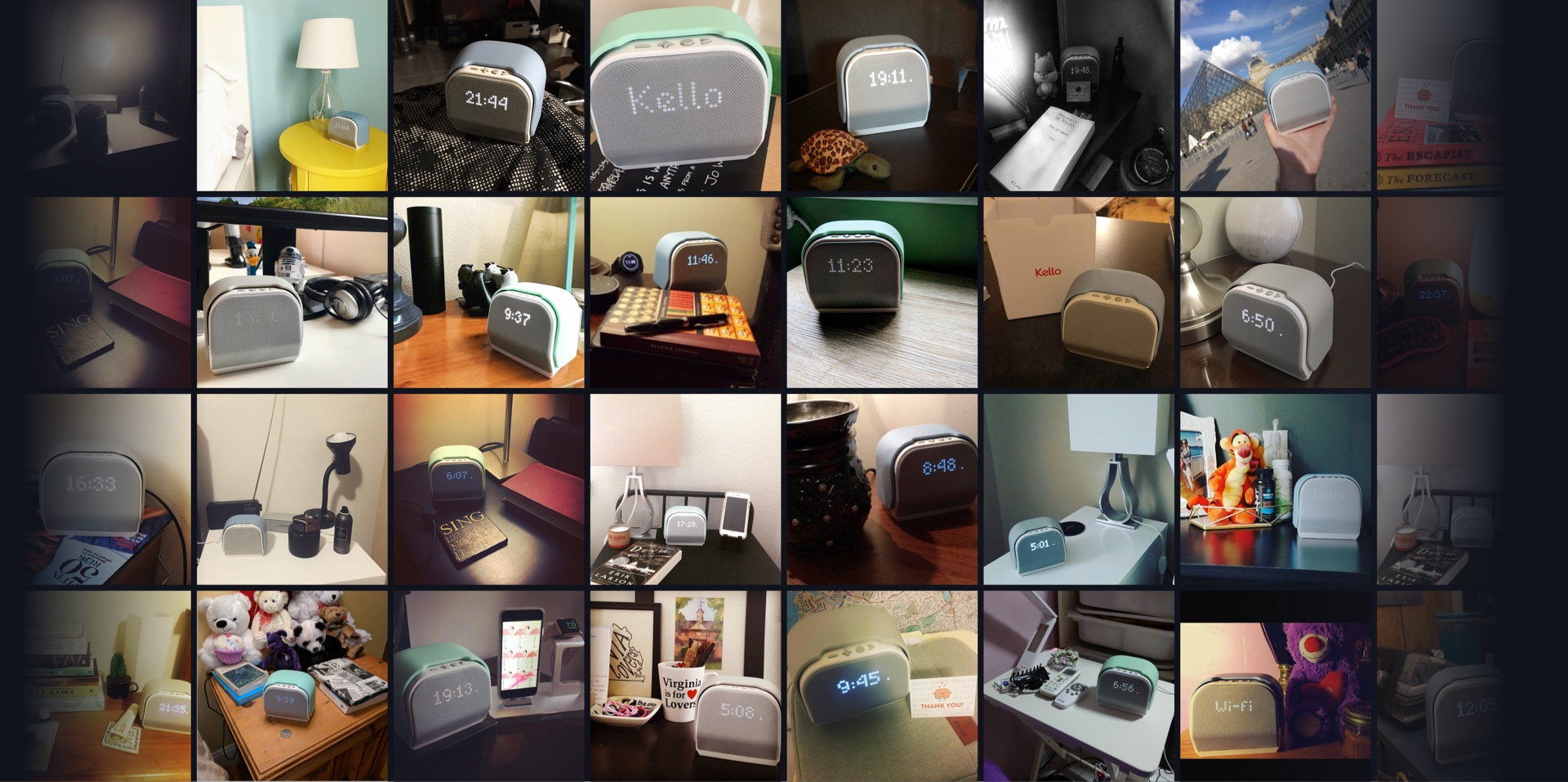

After months of fine-tuning and troubleshooting, we shipped 3,200 units worldwide.

That was it. 3 years of hard work, materialized in our hands.

We got an overwhelming response from people all over the world, excited to try their Kello. People actually took pictures of their device on their nightstands!

One customer even sent us a long email explaining how much our journey resonated with her own. At first, she almost regretted putting money into what felt like just vaporware. But as months passed and she went through an intense period of introspection, rebuilding her mental health, she watched our product take shape, newsletter after newsletter, until the day she finally held it in her hands.

For her, it was so much more than just an alarm clock. And for us, that email was truly unforgettable.

The harsh reality

Building a working prototype with almost no money? Check ✅

Running a killer crowdfunding campaign? Check ✅

Manufacturing 3,200 units? Check ✅

Now, the investor money should start rolling in… right?

We worked relentlessly to raise additional funding. But venture capitalists weren’t biting. Hardware is hard, and VCs weren’t interested in a consumer product like ours. "Too risky", "not in our investment thesis".

It's important to understand the difference in mindset between venture capitalists and business angels. VCs are typically looking for startups that can deliver 10x returns. They're looking for massive scalability.

Business angels, on the other hand, often focus more on whether a product can be profitable in a reasonable timeframe. They care about solid margins, clear unit economics, and realistic market entry.

In hardware, while the upfront cost can be significant, the path to profitability is often more straightforward than SaaS. You build something tangible, you sell it for more than it costs to make, with a great margin (70% at least) and you reinvest or redistribute.

With a well-designed product, a clear go-to-market, and good distribution, business angels can quickly see the potential and that’s exactly what they saw in our case: a credible plan to make money, not just raise it.

But one day, everything fell apart.

One morning, I got a call from the factory director. His voice was tense. He looked out his window and saw bulldozers rolling onto the property. The landlord had decided to sell the land, and the entire factory had just three months to pack up and relocate.

That meant no new production, no way to manufacture another batch that would give us fresh money and keep us afloat. We had fought hard to keep Kello alive, but this was it.

We pulled the plug.

What comes next?

What a crazy ride. Kello taught me more than any MBA ever could about building, failing, and pushing through when everything feels impossible.

Today, thousands of people still wake up with Kello. Almost ten years later, the product is still running, solid and reliable. And I now get just as much joy from building and growing product teams as I did from developing hardware back then. There’s something deeply rewarding about guiding others through the chaos of creation, watching a product evolve and hopefully succeed.